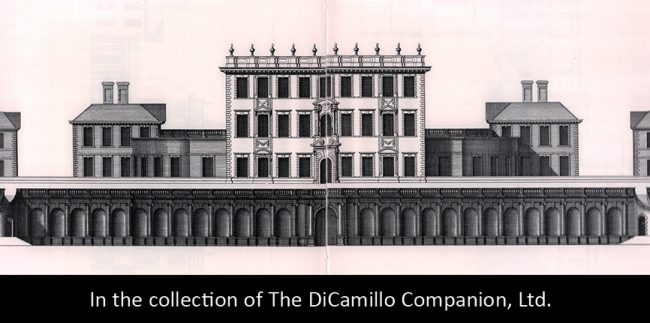

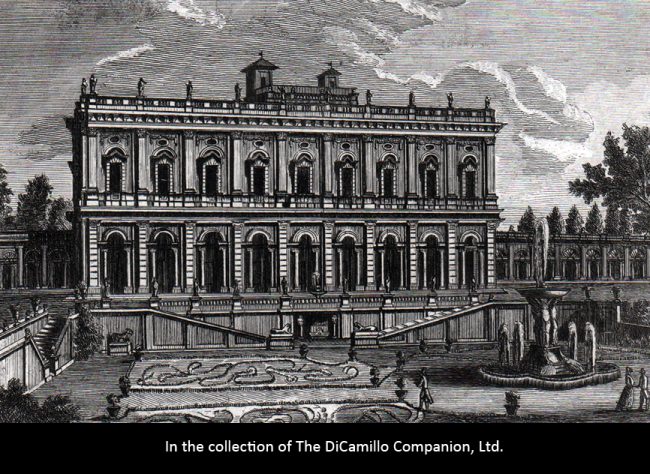

The garden facade from the 1717 edition of "Vitruvius Britannicus"

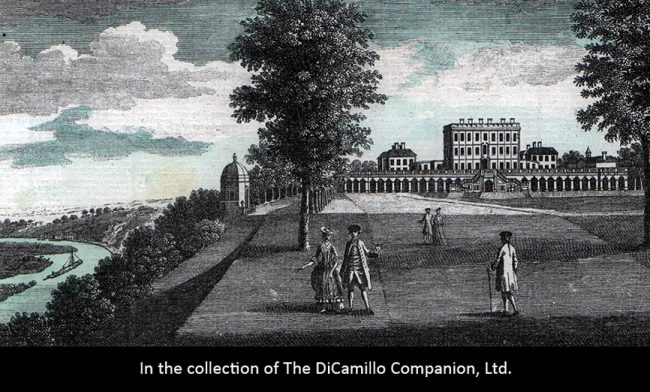

The garden facade, with the Octagon Chapel on the left, from an 18th century hand-colored engraving.

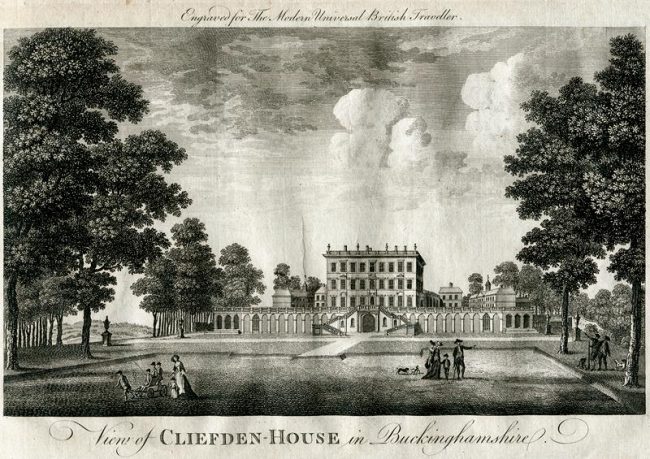

The garden facade, engraved by J. Cooke, London, 1779-90, for "The Modern Universal British Traveller."

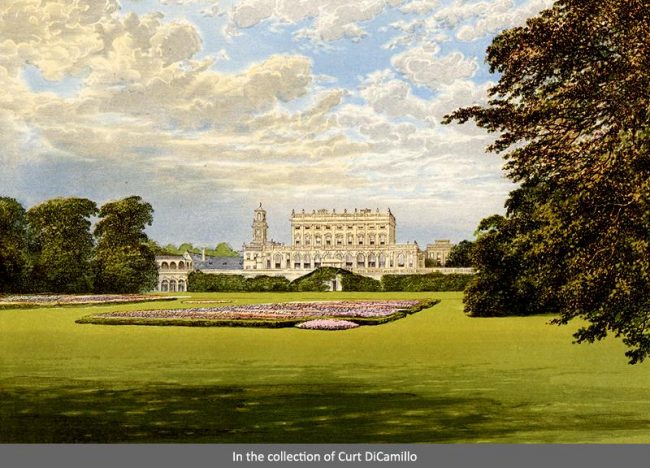

The garden facade from "Morris's County Seats," circa 1880.

The garden facade at dusk in 2017

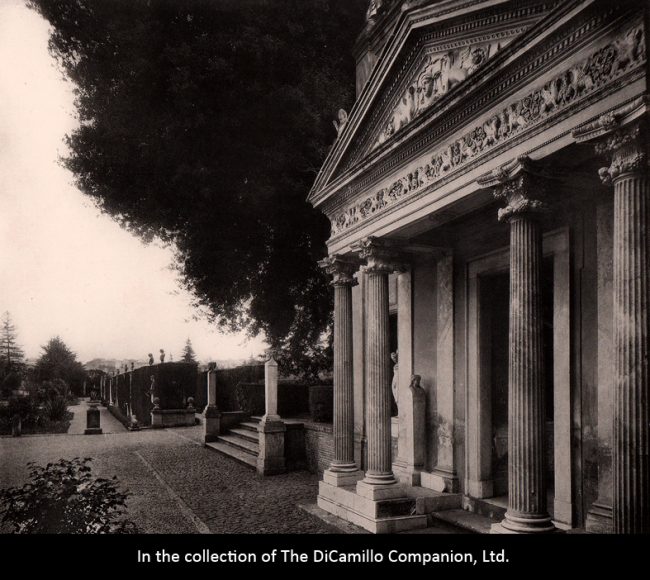

The Villa Albani, Rome, from "The Educational Tour of Ancient and Modern Rome," 1807. The 19th century rebuilding of Cliveden was likely based on the Villa Albani.

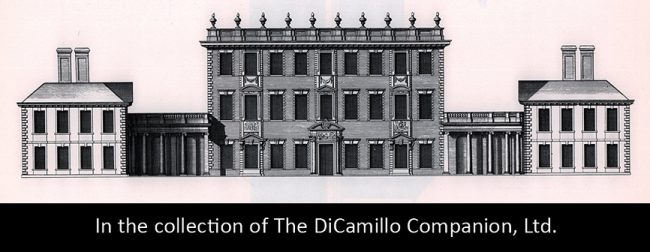

The entrance facade from the 1717 edition of "Vitruvius Britannicus"

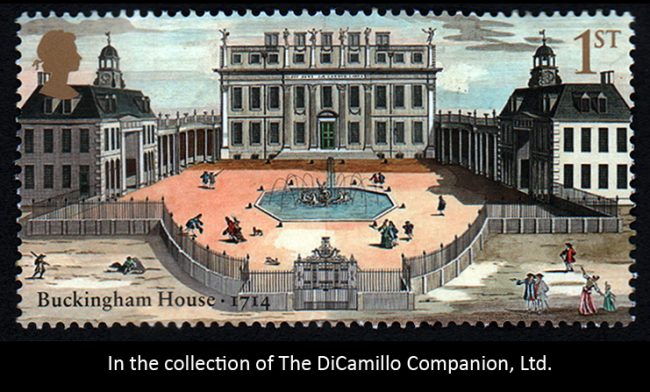

Buckingham House in 1714 from a 2014 stamp. Winde designed this house, whose similarities to his Cliveden are striking.

The grand staircase in 2017

The dining room in 2017

Ground floor hallway in 2017

Nancy Astor's Bedroom in 2017

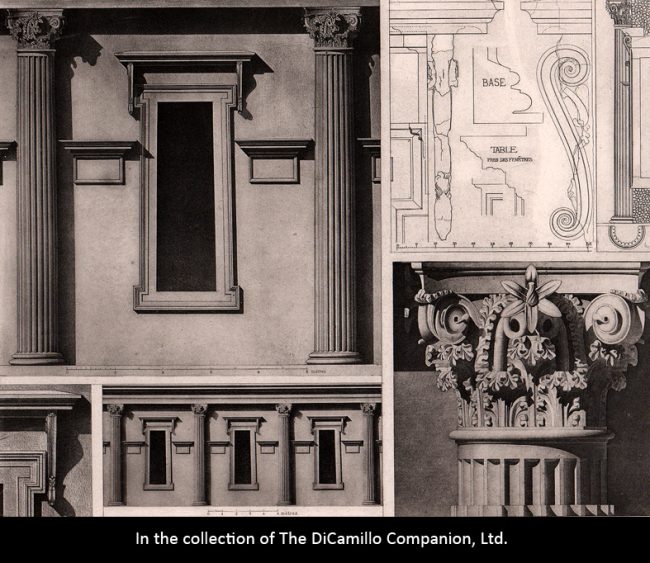

Ducal wall plasterwork

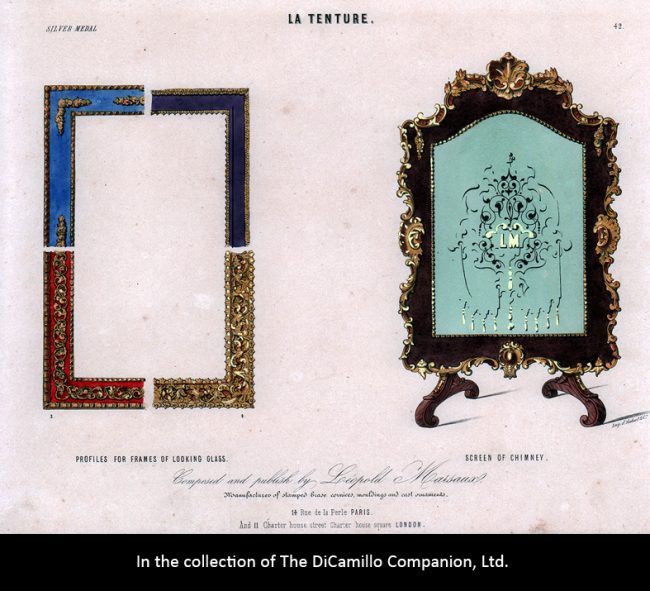

An 1880 Allard print for a frame and chimney. William Waldorf Astor used Allard in the redecoration of Cliveden.

The Octagon Temple (aka the Summer House and the mausoleum) from an 1876 issue of "The Art Journal"

The Octagon Temple at dusk in 2017

The Fountain of Love in 2017

The Long Garden in 2017

The garden 2017

The Water Tower in 2017

A 1906 photo of the entrance to the Bosco at the Villa Albani, Rome. Astor was inspired by Italian gardens like this in the layout out of Cliveden's gardens.

An 1890s heliogravure showing fragments from Palestrina. William Waldorf Astor was very likely influenced by the ruins of Palestrina in his garden design for Cliveden.

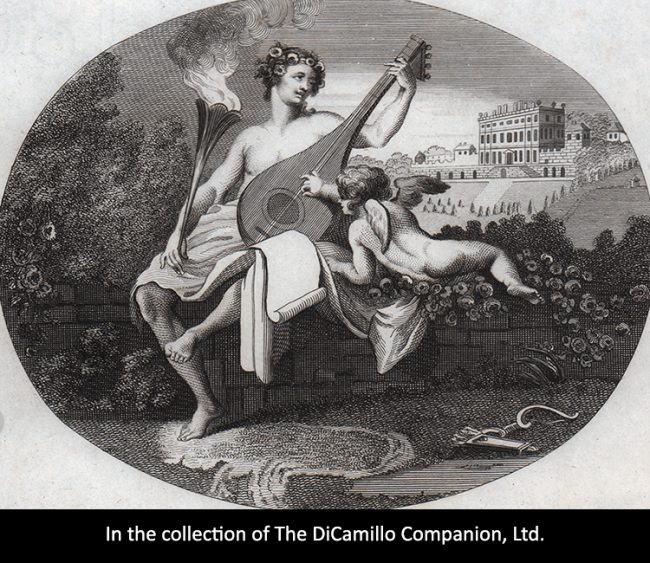

An August 1, 1740 ticket to the masque "Alfred," with Hymen and Cupid in the foreground and Cliveden in the background. The first performance of the masque was held on the grounds of Cliveden.

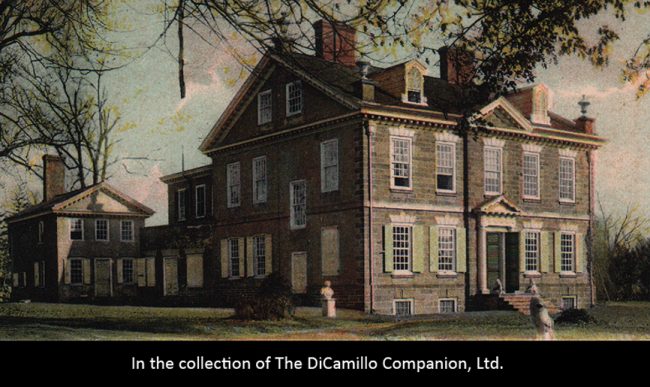

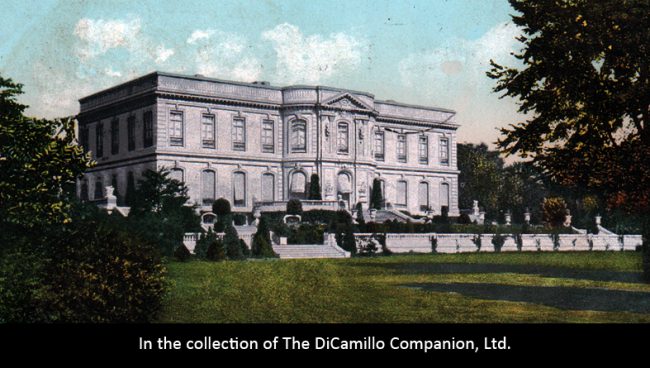

Cliveden, Philadelphia, from a 1907 postcard.

The Elms, Newport, Rhode Island, from a 1907 postcard. William Waldorf Astor purchased Madame de Pompadour's 18th century dining room from the Chateau d'Asnieres for the Dining Room at Cliveden. The Elms was modeled on Chateau d'Asnieres.

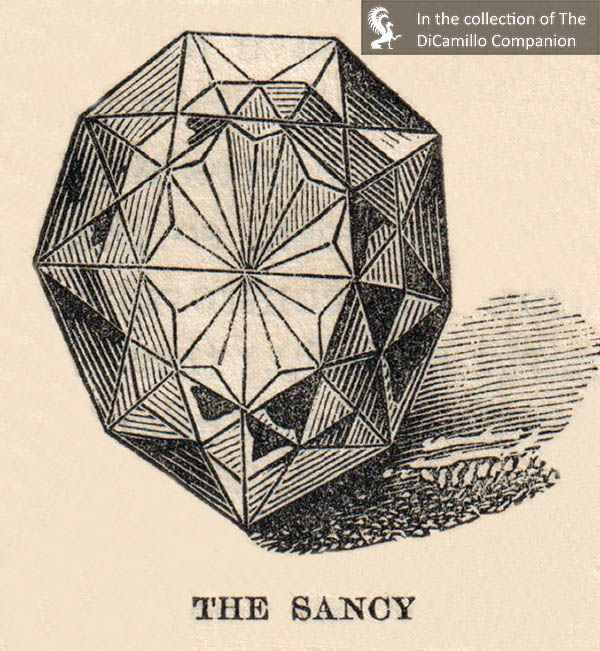

The Sancy Diamond as it appeared in the mid-19th century. Illustration from an 1866 issue of "Harper's New Monthly Magazine." William Waldorf Astor gave the 14th century, 55-carat, pale yellow Indian diamond as a wedding gift to his daughter-in-law, Nancy Astor.

An 1806 engraving of George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, for whom Cliveden was originally built.

Built / Designed For: The original 17th century house was built for the 2nd Duke of Buckingham.

House & Family History: "It is grievous to think of it falling into these hands!" Those were the words of Queen Victoria, who had spent much time at Cliveden and who famously called it a "bijou of taste," when she heard that the 1st Duke of Westminster had sold Cliveden, one of the great houses of England, to William Waldorf Astor on August 15, 1893 for $1.25 million (approximately $167 million in 2014 inflation-adjusted values). It was the first time in its long history that the house had been owned by a non-aristocrat, and, an American at that! But the queen was wrong. Astor was the perfect custodian for Cliveden, and the dynasty that he established proved to be one of the most enduring in the house's long history. William Waldorf Astor, with his passion for old places redolent of history, was immediately taken by Cliveden and its 230-year-history and stunning position towering above the River Thames. And it certainly couldn't have hurt that Cliveden had been the seat of three dukes, a Prince of Wales, and an earl! And, to add even more spice to the mix, since the 17th century Cliveden has been associated with enormous wealth and powerful cliques. The house that Astor bought is the third to be sited on this spectacular outcropping of tall chalk cliffs (the name was originally spelled Cliffden). The first was built around 1666 for George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, the famous Restoration rake, author, lover of pleasure, and friend of King Charles II (the duke was the "B" in the CABAL, a group of five Privy Councillors who were favorites of king and who supposedly had enormous sway over government policy in the 17th century). The Duke of Buckingham built his house as hunting lodge, a place of escape from the capital, but still close to the centers of power (Windsor is five miles away and London less than 30), where he could spend relaxed times enjoying life with his friends and mistress, the Countess of Shrewsbury. His architect was William Winde, one of the most important country house architects of the late 17th century and the designer of Buckingham House, today's Buckingham Palace, with which Cliveden shared design elements. In spite of his debauchery, Buckingham was intelligent, progressive, and ahead of his time. One hundred years before Capability Brown came along and changed the English landscape, the duke chose a site for Cliveden that was based on its picturesque setting and its view, not its practical considerations, something that Brown would have done, but that was virtually unheard of at the time. What most people looked for when positioning a house was a sheltered location, preferably in a valley, not one that stood high and proud on a hill where it would be buffeted be strong winds, rain, and storms. The famous diarist John Evelyn was one of the few who understood what Buckingham had achieved. We have this from Eveyln's diary entry for July 22, 1679: "I went to Cliffden, that stupendious natural Rock, Wood & Prospect of the Duke of Buckingham's… this a romantic object & the place altogether answers the most poetical description that can be made of a solitude, precipice, prospects & whatever can contribute to a thing so very like their imaginations." The Duke of Buckingham died on April 16, 1687 and was buried in the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey amid great splendor. In spite of this pomp and circumstance, he died in enormous debt with no legitimate heirs, so all of his property, including Cliveden, was sold to pay his creditors. Nine years later, in 1696, George Hamilton, 1st Earl of Orkney, purchased Buckingham's great house and gave it new life. The new owner was a talented, modest, good-natured, and well liked soldier. He also served as the Governor of Virginia from 1710 until 1737 (even though he never visited America) and became Britain's first field marshal in 1737, just weeks before his death. And he was a loving custodian of Cliveden. Orkney's primary contribution to the estate was the laying out of the gardens, the basic designs of which still exist today, and the hiring of Thomas Archer to add the wings and colonnades to Winde's original house. In the garden the Earl engaged the Venetian architect Giacomo Leoni to design two lovely follies: Blenheim Pavilion (Orkney had been one of the stars at the Battle of Blenheim, serving under the Duke of Marlborough at one of the most important European battles of the 18th century) and the Octagon Temple, the latter of which was converted into a chapel and mausoleum by William Waldorf Astor. Orkney's standing was such that the king, George I, was his dinner guest at Cliveden in September of 1724. At Orkney's death on January 29, 1737 Cliveden was inherited by his daughter, Anne, who leased the great house to her friend, Frederick, Prince of Wales, for the sum of £600 per year (approximately £1 million today). The prince lived here with his large family until his death at the age of 44 in 1751. Frederick is almost forgotten today because of his early death and because his eldest son stepped into his father's shoes and became king as George III, but it's worth mentioning what an amazing man he was. Frederick was the first member of the British royal family to actually interact with commoners, he helped popularize the game of cricket, he was an accomplished musician and art connoisseur (eight of the van Dycks that Frederick purchased and displayed at Cliveden remain in the Royal Collection today), and he was possibly the most progressive and enlightened of all the Hanoverians. And it's not much of a leap to conclude that George III grew into the kind and generous man he did because of his happy childhood at Cliveden under the enlightened eye of his father, Frederick. In 1740 Frederick commissioned Thomas Arne to compose the opera "Alfred" (about England's greatest medieval king, Alfred the Great) as a masque to celebrate the accession of his grandfather, King George I. The first performance was held at Cliveden on August 1, 1740, with the composer himself conducting in the presence of the prince and princess of Wales. The reason we remember "Alfred" today is for its finale, "Rule, Britannia!," which has become the unofficial national anthem for Britain, the first bars of which can be heard on the soundtrack of virtually every movie and television show associated with England. It's hard to overestimate how powerful this little bit of music has been. Wagner said that the first eight notes of "Rule, Britannia!" embodied the entire character of the British nation. Beethoven, Thomas Attwood, and Sir Alexander Mackenzie all used the theme in their compositions. And it all happened at Cliveden and all because of Frederick, Prince of Wales! After Frederick's death in 1751, Anne, who had become Countess of Orkney in her own right at her father's death, took back Cliveden and made it her primary English seat until her own death in 1756. Her descendants continued to live quietly and uneventfully at Cliveden until 1795, when the great house burned to the ground, leaving only the wings and colonnades standing. Of the few furnishings that were saved from the fire, the most valuable were the famous early 18th century Brussels tapestries that commemorate the great English victory at the Battle of Blenheim. Made for the Earl of Orkney as part of the "Art of War" series, they hang today in the Great Hall at Cliveden. After the fire the family lived in the wings and the main block remained a ruin for 30 years. It wasn't until 1824, when Cliveden was purchased by Sir George Warrender, that the great country house began to shine once again. Sir George, known to his friends as "Sir Georgeous," was one of the great bon vivant of the 19th century. He was helped considerably in this love of life by inheriting, in 1799 at the age of seventeen, a Scottish fortune and a baronetcy. Sir George hired the Scottish architect William Burn to rebuild the burned-out main block of Cliveden, once again linking the house to the colonnades and wings and giving him the perfect party house! Sir George was known as a faultless host, giving his guests enormous freedom, good food, the best wine, and exceptional company. Once again, Cliveden was serving the purpose for which it had originally been built. Sir George died in February 1849 and Cliveden was inherited by his brother, John, who sold the house to the 2nd Duke of Sutherland in June of the same year as a retreat for his wife, Duchess Harriet. But, just months after the duke and duchess moved in, the house burned down again. On November 15, 1849 that Queen Victoria saw the smoke from her window in Windsor Castle and called the fire engines to Cliveden to extinguish the blaze. Though the fire in the main block could not be contained, the colonnades were pulled down to prevent the fire spreading to the wings, a plan that saved significant sections of the house (the duke and duchess were at their Scottish estate at the time). Once again, the main block was left in ruins, but the Sutherlands, among the richest of the Queen's subjects, wasted no time in hiring their favorite architect, Sir Charles Barry, to rebuild the house. Barry had become renowned as the architect of the new Houses of Parliament and one can see echoes of that famous building in the final product he provided for the duke and duchess. The Italianate villa that Barry built on the foundations of the two earlier houses is acknowledged to be one of his masterpieces. This house, which still stands today, owes much of the inspiration for its design to the Duke of Buckingham's original house and can justifiably be called a palace. And, speaking of palaces, we can't leave Barry and not mention the work he did at the Sutherlands' London home, Stafford House (now Lancaster House), possibly the most spectacular townhouse in the capital. Queen Victoria supposedly said, upon visiting her friend, the duchess, at Stafford House, "I have come from my house to your palace." And, indeed, Stafford House was grander than Buckingham Palace at the time, or any of the queen's other London residences. Ironically, today Lancaster House is frequently seen in films as the interior of Buckingham Palace, the most famous example of which is probably the 2013 episode of "Downton Abbey" entitled "The London Season." The Sutherlands brought Cliveden to new heights, where they entertained lavishly and frequently. Duchess Harriet, a Howard who had grown up at Castle Howard, was a progressive Whig who hosted many of the era's liberal leaders at her palace by the Thames, even having Giuseppe Garibaldi, the darling of British progressives who had united Italy, come to stay in 1864. The Liberal Prime Minister, William Gladstone, was one of the duchess's closest friends, a frequent guest, and the man who helped Harriet make Cliveden a major force in the progressive movement. It was probably here, in the 1860s, that the very first "Cliveden Set" was born—representing high minded and progressive Whigs. This Cliveden Set appears in Cliveden's history again—with a very different meaning. All of this was conducted in Barry's luscious new interiors filled with world class art. There were paintings by Canaletto, Velazquez, Poussin, and Winterhalter and sculpture by the best 19th century artists. In 1855 the duchess commissioned the French painter Auguste Hervieu to create "The Four Seasons" mural on the staircase ceiling, using her eldest son and three of her daughters as the models for the seasons. This is one of the very few things that has survived from the Sutherlands' time at Cliveden, the rest having been lost in the Astors' extensive rebuilding of the interiors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was the Prime Minister, William Gladstone, who penned the Latin inscriptions that boldly proclaim Cliveden's importance on the frieze on all four sides of the house: "Constructed upon foundations laid long before by George Villiers Duke of Buckingham in Charles the Second's reign." "Completed in the year of Our Lord 1851 when Victoria had been Queen by God's grace for fourteen years." "Restored by George Duke of Sutherland and Harriet his wife on the site where two houses had previously been burnt down." "Built by the skill, devotion and design of the architect Charles Barry in 1851." After Duchess Harriet's death in 1868, her eldest son, George, 3rd Duke of Sutherland, sold Cliveden to his brother-in-law, Hugh Grosvenor, Earl Grosvenor. This wasn't just the sale of a big house between two rich relatives—Grosvenor had fond memories of Cliveden, as it was here in 1852 that he spent his two-week honeymoon. The Gower family left Cliveden with some sadness, but also with affectionate memories, as evidenced by the words of Lord Ronald Gower, the youngest son of the 2nd Duke of Sutherland: "Many happy days have we passed among these woods and on that river. The very name of Cliveden recalls the hawthorn and the may, the fields in June, the carpets of primroses and violets, the scent of the cowslips and the thyme, the hum of bees, and the music of the feathered choristers in the woods." Hugh Grosvenor, a kind and very generous man who was liked by almost everybody, became the wealthiest man in Britain in 1869 upon the death of his father, the 2nd Marquess of Westminster. Literally because he was so rich, Queen Victoria created him the 1st Duke of Westminster in 1874, but he was more than a rich aristocrat. He supported legislation to reduce cruelty to women in the workplace, was president of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the president of five London hospitals, and a founder of the National Trust. And, like later owners of Cliveden, Waldorf and Nancy Astor, the duke was a teetotaler and supporter of the temperance movement. Cliveden was the smallest of the duke's homes, and one he didn't keep for long. In 1893, after just 25 years of ownership, the 1st Duke of Westminster sold Cliveden to the richest man in the world: William Waldorf Astor. And it was under the Astors that Cliveden reached its most glittering zenith. Astor took on Cliveden with gusto—possibly at no other point in its long history was the house lavished with so much care and attention. The interior was radically rebuilt to incorporate William's late Victorian ideas of comfort and to highlight his collection of art, furniture, and tapestries. The most profound interior transformation was the sweeping away of three rooms: the Entrance Hall, the Morning Room, and the Staircase Hall to allow for the creation of today's Great Hall. The new Great Hall was installed with a large 16th century fireplace from a chateau in Burgundy and then the entire room was fitted with English oak paneling with Corinthian columns, all part of Astor's plan to make Cliveden as much like a Roman palazzo as possible. One of William's greatest triumphs at Cliveden is the French Dining Room. On a visit to Paris in 1897, he was shown, in a dealer's showroom, the gilded paneling from Madame de Pompadour's 18th century dining room at the Chateau d'Asnieres. Realizing the proportions were exactly the same as those of the dining room at Cliveden, he purchased the paneling, table, and chairs, and had the entire room reconstructed at Cliveden as the French Dining Room. He then engaged the Paris firm of Allard to produce a plaster frieze of hunting scenes, as well as the matching furniture for the room. The story of the French Dining Room perfectly illustrates William's talent in identifying desperate elements and bringing them together to create a harmonious whole. Astor was extremely interested in the history of Cliveden and installed images of many the ladies who presided over the great house. In the Great Hall hangs a portrait of Anna Maria, Countess of Shrewsbury, mistress of the Duke of Buckingham, who inspired him to build the original 17th century house. Elizabeth, Countess of Orkney, is one of the carved figures on the staircase in the Great Hall, while a portrait of Augusta, Princess of Wales, hangs over the grand staircase. Harriet, Duchess of Sutherland, Queen Victoria's dearest friend, presides magnificently in the Dining Room. But the chatelaine with the greatest verve is John Singer Sargent's 1909 portrait of Nancy Astor, William's daughter-in-law, and the unchallenged and dominating star of the Great Hall. But he didn't stop with the house. Astor virtually recreated the grounds at Cliveden. He installed statuary everywhere and created new gardens with unbridled enthusiasm. In rapid succession, he installed the Cliveden Maze, the Japanese-style Water Garden (believed to be the first Asian-inspired garden in England, complete with a pagoda on an island that Astor purchased from the Bagatelle estate in Paris), the imported California redwoods, and the Long Garden, an Italian style garden designed by Norah Lindsay, one of first professional female landscape designers. And he restored the glorious parterre, at four acres, one of the largest in Europe. But it is statuary that Astor was most passionate about and that's what dominates the Cliveden garden he left to posterity. Ancient marble sarcophagi and oil jars from Rome and well heads from Venice are complemented by modern and ancient sculpture in profusion. The most famous of these sculptures is probably the Carrara marble shell fountain that greets visitors as they approach the great house. Known as the "Fountain of Love," it was commissioned by Astor in 1897 and sculpted by Thomas Waldo Story (under whom Astor himself studied) in Rome. The garden prize is undoubtedly the Borghese Balustrade on the parterre, a 17th century travertine balustrade that William purchased from the Villa Borghese gardens in Rome. The garden is nothing less than a triumph of William Waldorf Astor and Italy. Astor also installed or rebuilt follies throughout the grounds, the most notable of which is probably the Octagon, or Summer House, an octagonal, domed teahouse built for the 1st Earl of Orkney in the 18th century. This folly was turned into a lavish chapel and mausoleum by William in 1893 and contains the remains of the viscounts Astor, as well as those of the famous Nancy Astor and her son from her first marriage, Robert Gould Shaw, scion of an old Boston family. In 1906 William gave Cliveden as a wedding gift to his eldest son, Waldorf, who was marrying Nancy Langhorne of Virginia. But the generous William didn't stop there. He was so happy with his future daughter-in-law that he gave the young couple another astonishing wedding gift: the famous Sancy Diamond. The Sancy (see "Images" section), a pale yellow diamond of 55.23 carats, probably had its origins in 14th or 15th century India, the source of the world's diamonds until the discovery of new mines in Brazil in the 18th century. The legendary stone was later owned by European kings and courtiers, until it came into the hands of Nicolas de Harlay, seigneur de Sancy, from whom it got its name. De Sancy, a gem connoisseur and power broker, acquired the stone in the 16th century and used it as a tool in the game of realpolitik. The great diamond eventually ended up in the collection of the kings of France, from whom it was stolen (along with the French Blue, known today as the Hope Diamond) during the French Revolution. The Astors owned it for 72 years (Nancy frequently wore the diamond in a tiara on state occasions; it could also be worn as a brooch), until it was sold in 1978 by the 4th Viscount Astor for $1 million to the Louvre. It remains in that great museum's collection today—a lasting testament to a magnificent collector with an amazing eye and the pocketbook to bring his visions to life. Nancy Astor, a forceful personality, to put it mildly, took Cliveden firmly in hand after her wedding to Waldorf. She redecorated and modernized the house, brightened up its dark interiors, and installed electricity. It's safe to say that Cliveden reached its greatest heights during the time of Waldorf and Nancy Astor. Certainly the old house had never been the center of so many parties, dinners, lunches, and receptions. Indeed, an invitation to Cliveden was one of the most prized in Britain in the first quarter of the 20th century. Nancy, who became the first woman to sit in the House of Commons, entertained at Cliveden endlessly—and democratically—with an eclectic assortment of aristocrats, writers, artists, left and right-wing politicians, and even self-made working men! Even the butlers at Cliveden were famous. Edwin Lee rose from a Shropshire farming family to become one of the premier butlers in the world—Nancy Astor, a very demanding employer, expected nothing less. In fact, the novelist Kazuo Ishiguro based his creation of Stevens, the butler in his 1989 book "The Remains of the Day," on Mr. Lee, a part famously played by Anthony Hopkins when the novel was brought to the silver screen by Merchant Ivory in 1993. Between the World Wars Cliveden was an important center of political and social activity. Waldorf and Nancy made the house a popular gathering place for influential people who became known as "The Cliveden Set," primarily for their German sympathies prior to World War II. Though later evidence seems to indicate that Nancy Astor did not so much favor Germany, as want to avoid another world war, the phrase still causes us today to think of members of the British upper classes who favored accommodation with Nazi Germany. Nancy was a larger-than-life character who inhaled all the oxygen in any room she occupied. She had strong opinions on virtually every subject, something she didn't hesitate to share with anybody who would listen, and even those who wouldn't! She sat in the House of Commons for 26 years, was a passionate Christian Scientist, a committed teetotaler (a conviction she shared with her husband), and devoted friend to many people. She was also extremely difficult, had a fiery temper, and was an uncomprehending and difficult mother. Such was her stature that the BBC produced a 1982 mini-series about her entitled "Nancy Astor"—what else?! In 1942, when the future for the great houses of England looked very bleak, Waldorf gave Cliveden to the National Trust, together with an endowment of £250,000 (approximately £10 million today), with the understanding that the Astor family could continue to live at the House as long as they wished. A further provision in the agreement stated that, should the family cease to live at Cliveden, they wished that the House should be used "for promoting friendship and understanding between the peoples of the United States and Canada and the other dominions." Waldorf, whose health had been delicate for most of his adult life, died in 1952 at the age of 73. Nancy died in 1964 at the age of 84 mired in the mists of dementia. Their eldest son, Bill, had taken up residence in Cliveden years before, and it was during his tenure that one of the great British political scandals of the 20th century occurred at Cliveden. On July 8, 1961, during a weekend house party at Cliveden, John Profumo, a government cabinet minister and the Secretary of State for War, was introduced to the naked call-girl Christine Keeler by the swimming pool. Profumo, a married man, began a six-month affair with Keller that ended with his resignation from the government in 1963, after it was discovered that Keeler had, at the same time she'd been seeing Profumo, also been in a sexual relationship with a Russian spy. The Profumo Affair erupted into national scandal that brought down the government of Harold Macmillan in 1964. Though the kind and gentle Bill Astor had nothing to do with the party (it was hosted by his tenant Stephen Ward, who committed suicide over the scandal and ensuing press attention), it tarnished Bill's reputation and that of Cliveden's. The intense stress very likely shortened Bill's life (he died in 1966 at the age of 58) and ultimately led to the Astors leaving Cliveden for good in 1968. During the 1970s Cliveden served as an overseas campus of Stanford University, and in the 1980s it was converted into a five-star hotel, a purpose which it continues to serve brilliantly today. (This history of Cliveden was written by Curt DiCamillo for the 2017 book, "Villa Astor: Paradise Restored on the Amalfi Coast." © 2017 Flammarion).

Collections: The grounds contain a collection of garden statues that includes Roman antiquities acquired by William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor. On June 5, 2025, Bonhams London will auction a turquoise and diamond tiara purchased at Cartier's London shop in 1930 by Waldorf Astor, 2nd Viscount Astor, as a gift for his wife, Nancy Astor. The tiara has an estimate of estimate of £250,000-350,000.

Garden & Outbuildings: The house is surrounded by 375 acres of superb landscape gardens, a large part of which were laid out during William Waldorf Astor's tenure. Astor, who was very taken by ancient (particularly Roman) culture and sculpture, was probably influenced in his garden design by the ruins of Palestrina (see photo in "Images" section). There is also the Rose Garden designed by noted English garden expert Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, the Canadian War Memorial Garden. Blenheim Pavilion, the Ilex Grove, the Amphitheatre, the River Walk, and the Yew Tree Walk. The grounds are also notable for their delightful statuary, with the most prominent feature being "The Fountain of Love," which stands at the end of a broad entry avenue at the main approach to the house. Parts of the gardens date back to the 16th century, though most are of more recent vintage, and much of the statuary was added by the Astors. It was revealed on June 29, 2003 by "The Independent on Sunday" that the National Trust is planning to sell some of its land at Cliveden to developers; this would be the first time the Trust has made such a move. The trust plans to sell dozens of acres of land around the Cliveden Estate to a private developer for the construction of 200 executive style homes. The NT is expected to gain around £80 million from this scheme. (We are grateful to BritainExpress.com for contributing much to this history of the garden at Cliveden).

Chapel & Church: The Octagon Temple (see "Images" section), also known as the Summer House and the mausoleum, contains the ashes of William Waldorf Astor and other members of the Astor family. William Waldorf converted the 18th century garden folly into a chapel in the late 19th century, soon after he purchased Cliveden.

Architect: Crace & Sons

Date: 1890sArchitect: Giacomo Leoni

Date: Circa 1735Architect: Rupert Lord

Designed: Redesigned House for The National Trust to accommodate hotelArchitect: Thomas Archer

Date: Ante 1717Architect: Charles Barry Sr.

Date: 1850-51Architect: George Devey

Date: Circa 1857Architect: Henry Clutton

Date: 1857-61Architect: Henry Clutton

Date: 1869Architect: Robert William Edis

Date: 1886Architect: Henry Wise

Date: 1706Architect: Charles Bridgeman

Date: 1720sArchitect: Peter Nicholson

Date: 1813Architect: William Burn

Date: 1827-30Vitruvius Britannicus: C. II, pls. 70-74, 1717.

John Bernard (J.B.) Burke, published under the title of A Visitation of the Seats and Arms of the Noblemen and Gentlemen of Great Britain and Ireland, among other titles: 2.S. Vol. II, p. 226, 1855.

Country Life: XXXII, 808 plan, 854, 1912. LXX, 38, 1931. CLXI, 438, 498, 1977.

Title: Destruction of the Country House, The

Author: Strong, Roy; Binney, Marcus; Harris, John

Year Published: 1974

Reference: pg. 14

Publisher: London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

ISBN: 0500270052X

Book Type: Softback

Title: Cliveden: The Place and the People

Author: Crathorne, James

Year Published: 1995

Reference: pg. 109

Publisher: London: Collins & Brown Limited

ISBN: 1855852233

Book Type: Hardback

Title: Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600-1840, A - SOFTBACK

Author: Colvin, Howard

Year Published: 1995

Reference: pg. 610

Publisher: New Haven: Yale University Press

ISBN: 0300072074

Book Type: Softback

House Listed: Grade I

Park Listed: Grade I

Past Seat / Home of: SEATED AT EARLIER HOUSES: William de Turville, 12th century. Manfield family, 1600-66. SEATED AT CURRENT HOUSE: George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, 1666-87. George Hamilton, 1st Earl of Orkney, 1696-1737; Hamilton family here until 1821. Frederick, Prince of Wales, Hanover family, 1737-51. Sir George Warrender, 1824-49. George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 2nd Duke of Sutherland, 1849-61. Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 3rd Marquess of Westminster, 1st Duke of Westminster, 1868-93. William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor, 1893-1906.

Current Ownership Type: The National Trust

Primary Current Ownership Use: Hotel

Ownership Details: A National Trust property currently leased as a luxury hotel to London & Regional Properties. Some reception rooms are open to the public on a limited schedule.

House Open to Public: Limited Access

Phone: 01628-605-069

Fax: 01628-669-461

Email: [email protected]

Website: http://www.clivedenhouse.co.uk

Awards: Voted number 4 in the Top 10 Regal Wedding Venues in the UK in 2011 by "The Times."

Historic Houses Member: No