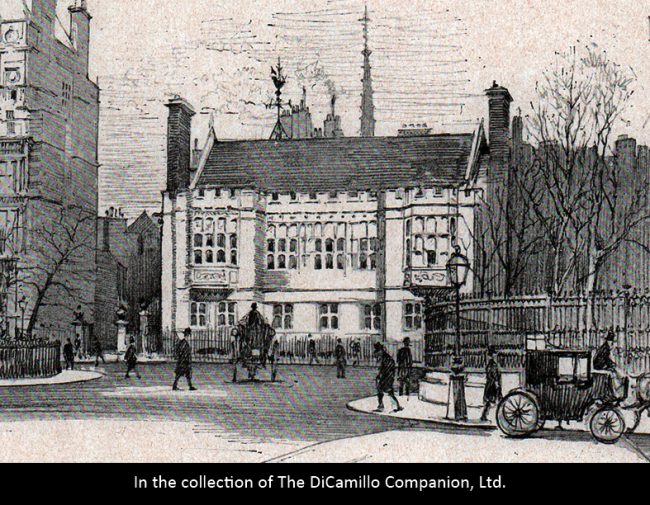

A drawing of the house from the Aug 8, 1902 issue of "The Building News"

The entrance facade

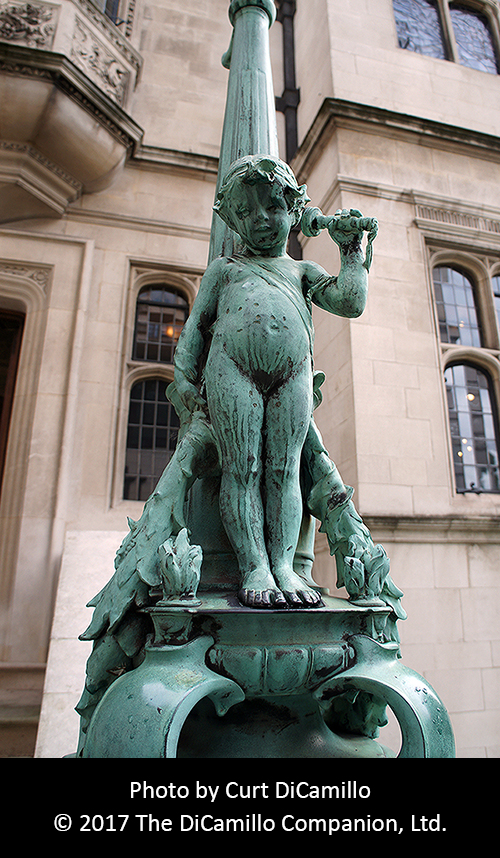

Putto and telephone entrance lamp

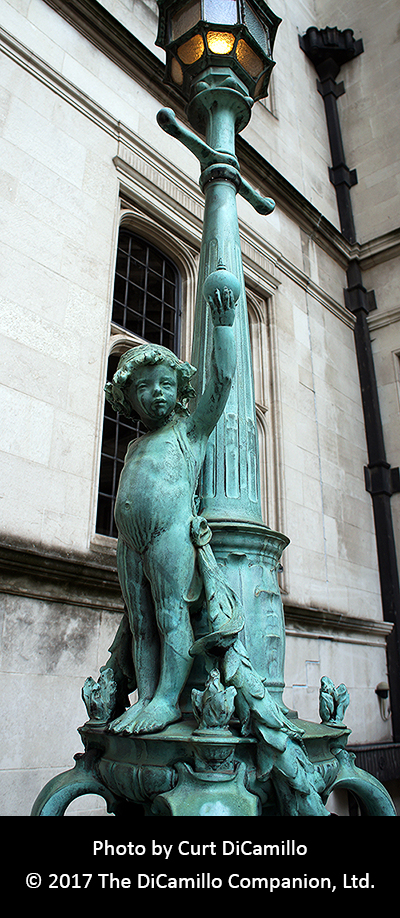

Putto and light bulb entrance lamp

The entrance hall

Hardstones in the entrance hall floor

Detail of fireplace in entrance hall

The Great Hall door

Overmantel of the Great Hall fireplace

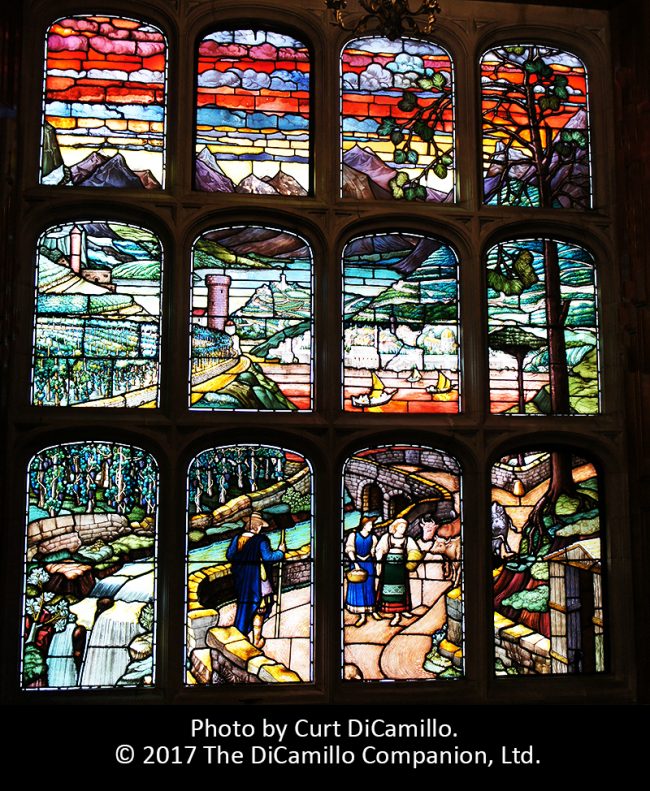

The "Sunset" window in the Great Hall

The Upper Entrance Hall

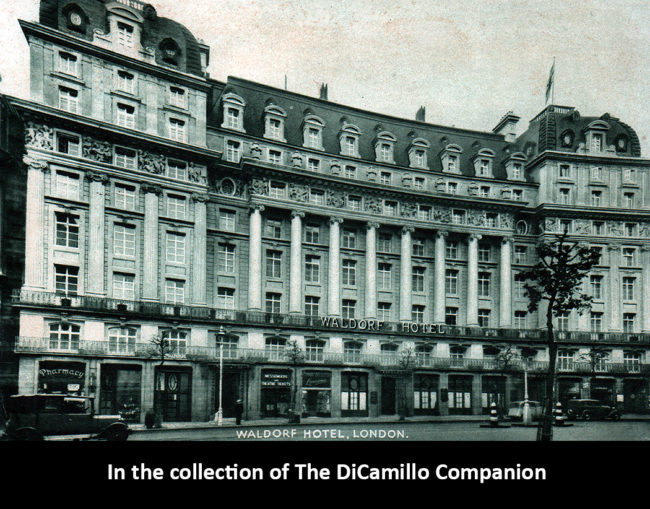

The Waldorf Hotel, London, founded by William Waldorf Astor. From a 1930s postcard.

Built / Designed For: William Waldorf Astor

House & Family History: Seldom has a house so completely reflected its owner's style and interests in art, architecture, and literature. A cross between a London club, an English country house, and an Oxbridge college, Astor House was William Waldorf Astor's art-filled retreat from the world. The great man probably spent the happiest times of his life planning and building this astonishing miniature London palace. Unique in Astor's menagerie of houses as the only one he built from the ground up, Astor House is an amalgam of Jacobean, Tudor, Gothic, and Renaissance styles whipped together into a gloriously successful whole. It was begun in 1893 and completed in 1895 as the Astor Estate Office, the global headquarters of the far-flung business interests that Astor managed, most particularly his vast New York City real estate holdings (he owned acres and acres of Manhattan). It was called "a castle of commerce" upon its completion and possibly helped inspire a famous New York City skyscraper that was once the world's tallest: the Woolworth Building. Built in 1913 by another wealthy American, Frank W. Woolworth, the famous Gothic-style Woolworth Building continues to be known today as "the cathedral of commerce." The piece of land that Mr. Astor purchased for his new house on Victoria Embankment was in an area of London known as the Temple. Before the Victoria Embankment was created by reclaiming land from the Thames in the 1860s and 1870s, the parcel Astor purchased originally fronted onto the River and was named for the Middle Temple, one of the ancient Inns of Court, the famous barrister-inhabited clutch of buildings and gardens near the Royal Courts of Justice. Astor, always intrigued and attracted by history, could not have failed to appreciate that the Wars of the Roses began in the Temple Gardens, where the white and red roses, representing the two warring sides, were plucked. Also nearby once stood the grand Tudor townhouses that Astor greatly admired and which he very probably sought to emulate in the building of his own townhouse. To achieve his architectural dreams, Astor employed the respected father-and-son architectural team of John and Frank Pearson. For John, the father, this would be the last work he completed before his death in 1897; his son Frank would later design the Tudor Village at Hever Castle for Astor. John Pearson was a master of the art of integrating architecture and the decorative arts, something he achieved masterfully at Astor House. Mr. Astor was determined to create the finest townhouse money could buy and told his architect that cost was no object. Pearson took Astor at his word and hired the best craftsmen and produced one of the finest Victorian houses in England. The cost of building and outfitting the house was reputed to have been £250,000, the equivalent of approximately £100 million today. It was said by Londoners that there was no plot of land in the metropolis that had ever had so much money spent on it. And, though he gave he gave his architects an enormous amount of freedom, there is no doubt that Astor was involved in the design of his dream house at every step of the way. In fact, the design, especially the interiors (most of which are virtually intact from Astor's time), tell us everything we need to know about the taste of the richest man in the world. Built of Portland stone (a hard limestone mined on the Isle of Portland in Dorset, and, not surprisingly, considering the client, the most expensive English building stone) Astor House is not huge—it's just two stories tall, but it does have castle-like battlements! Though it contained one bedroom (for Astor's use), the house was built, first and foremost, as the headquarters of the Astor business empire. In the basement was an enormous vault of 20 by 20 feet, supposedly the largest in Europe when it was installed. The vault was made of Portland cement and had a granite floor that was laid on a foundation of solid concrete, finished off by a steel vault door custom-made for Astor by Chubb (during the 1949-51 restoration work the vault was removed and replaced with office space). Because of this, Mr. Astor believed he had the second-strongest building in London, surpassed only by the Bank of England. He was probably right. As it was built near filled land and the river, which regularly flooded, the basements of Astor House were equipped with automatic pumps to protect the vault. Mr. Astor left nothing to chance. As one approaches Astor House today, possibly the most amazing sight, other than the house itself, is a large, galvanized steel weathervane topped by an enormous beaten and gilded copper ship. This is Columbus's famous flagship, the "Santa Maria," symbolizing to the world that this was the house of an American. As we will see, this is only the first of many illusions to the United States to be found in Astor House. But Mr. Astor was also proud of being an adopted Englishman, so there are examples of English symbolism throughout Astor House too. The exterior has a frieze of Tudor roses; there are beaten-lead grotesque rainwater heads on the downspouts; and then there's the elaborate iron fence, much like that of a nearby palace. Surprisingly, the façade facing the street does not contain an entrance; instead, it's located on the side, off of a little courtyard. The original doorway was swept away during the 1949-51 restoration, though the new doorway, with a lovely oriel window above it, is no less impressive. The original arched doorway was an homage to the founder of the Astor dynasty. Heavy bronze doors were framed by Corinthian-like columns presided over by the Astor coat arms and the carved words "The Estate Office of John Jacob Astor." All of this was majestically topped by a pediment with two heraldic beasts similar to those found at Hampton Court Palace. The twin bronze lamps by William Silver Frith on the entrance staircase feature fanciful putti playing with two examples of the latest technologies: magneto telephones and a filament light bulb. The lamps are crowned by bronze galleons, sculptures that very likely depict the "Niña" and "Pinta," the remaining two ships of Columbus's expedition, thus giving us, together with the weathervane, the full squadron of the famous ships of the 1492 journey. The case can be made that all of these symbolized the triumph of America, most particularly as it applies to the Astor family. John Jacob Astor sailed to America from the old world, just as Columbus had done, while the inventions that the putti are playing were invented by Americans. Thomas Edison, of course, invented the first workable electric light bulb, while Alexander Graham Bell, a Scotsman who became a naturalized American citizen, invented the first functional telephone. Astor, who loved the latest gadgets, made sure, of course, that his new house was installed with telephones and electric lights, something that was not de rigueur at the time. Client and architect shared an enthusiasm for colored stones, a passion that John Pearson satisfied in great abundance at Astor House. The Staircase Hall is the best example of this polychrome decoration: the floor is studded with green onyx, red porphyry, green jasper, and exquisitely colored marbles in a multiplicity of shapes. The fireplace, with four opulently green marble columns, was made of heavily-veined white Pavonazzetto, a variety of Carrara marble frequently used in Pompeii. This riot of color and stone would have reminded Mr. Astor of Rome, a city with which he was intimately familiar and one that was never far from his thoughts. The sumptuousness of the Staircase Hall continues with an exuberant stained glass skylight ceiling with the year 1895 in the center panel to celebrate the year the house was completed. Encircling the room is a striking red mahogany staircase with a balustrade that features newel posts carved by Thomas Nicholls that memorialize eight characters from Astor's favorite book: "The Three Musketeers." Though there was an Elizabethan style for such carved wooden figures on staircases (Hatfield House in Hertfordshire is possibly the best and most famous example), like so much else associated with Astor, his beautifully-carved figures, at 1.5 feet tall, are rather large. The walls of the Staircase Hall are covered in light-colored oak paneling that leads up to a colonnade of ten dark, highly polished solid mahogany Corinthian columns that surround the stairwell on the top floor. Continuing the literary theme, six of the columns are topped by carved figures, also by Nicholls, from American literature, including Rip Van Winkle, Hester Prynne from "The Scarlet Letter," and characters from "The Last of the Mohicans." One can only speculate that it's not a coincidence that "Rip Van Winkle" and "The Last of the Mohicans" took place in upstate New York, Astor's home state. To add further literary references, there is an oak frieze, just below the stained glass skylight, that features 82 carved characters, again by Nicholls, from Shakespeare plays. Each side depicts a different play: "Anthony and Cleopatra," "Macbeth," "Othello," and "Henry VIII." The last play shows a scene of the wedding of Henry to Anne Boleyn, which presaged Astor's later interest in the Boleyn family home of Hever Castle in Kent, which he purchased in 1903. Spanning the entire length of the building, the Tudor-Renaissance style Great Hall was the famous man's office and private domain. It had impressive dimensions: 71 feet long, 28 feet wide, and ceilings that soared to 35 feet. One entered into William Waldorf Astor's sanctum sanctorum through one of the most impressive features of an exceedingly impressive house: an enormous carved mahogany door divided into nine panels, each with a cast bronze silver-gilt figure of a woman from Arthurian legend set within in a Romanesque arch. Designed and executed by George Frampton, the panels feature images of Lyonors, La Beale Isoude, Enid, Alis La Beale Pilgrim, the Lady of the Isle of Avelyon, Elaine of Astolat, Morgan le Fay, and the Lady of the Lake. Triumphantly placed in the middle panel is the enthroned Queen Guinevere. Barely recovered from the lavishness of the door, one was immediately struck by the soaring open-timber hammerbeam roof, emulating that of a great Tudor hall; but, this being an Astor house, instead of the traditional English oak, the roof was made of solid Spanish mahogany. And, to add just that extra Astor touch, on top of the brackets supporting the roof were 12 gilded statutes carved by Nathaniel Hitch of characters from "Ivanhoe," another of the great man's favorite books. Even today, there is still probably no such roof anywhere else in the world. The polished hardwood floor was done up in octagonal and hexagonal patterns, while the French Renaissance style chimneypieces, also by Hitch, featured exuberant caryatids and atlantes carved from pencil cedar, an American wood from the juniper family noted for its fragrance. To complete the feeling of a luxurious medieval baronial hall (though the originals were anything but luxurious), there were gilded wrought iron chandeliers for artificial light. Natural light was provided by five windows that looked out majestically over the River Thames. The walls of the Great Hall were paneled with pencil cedar, punctuated by mahogany pilasters—Mr. Astor loved mahogany! For those waiting to see the richest man in the world, next to each fireplace (there were two—one at each end of the room, only one of which survives) there was a large inglenook with an elaborately carved bench, again by Hitch, behind which was an enormous 12-paneled stained glass landscape window that measured 11 feet high by nine feet wide. Minor masterpieces in their own right, these windows (both of which are extant) dominate the room with their robust and intense colors and their imaginary medieval Swiss scenes—the east window is entitled "Sunrise" and the west window "Sunset." The windows were manufactured by the English partnership of Clayton & Bell, who also did the stained glass skylight in the Staircase Hall for Mr. Astor, and are unusual in presenting to the viewer all 12 panels as a single integrated picture window, while also allowing each panel to be seen as a self-contained and complete scene when viewed up close. If one was expecting stained glass in the popular, medieval English style of William Morris, this wasn't it. Instead, Mr. Astor gave his house stained glass reminiscent of the great Gilded Age mansions of the American cities of New York and Newport, a milieu with which he was very familiar. All of this was encircled above by a frieze of 54 carved and gilded portraits by Hitch of famous historical and fictional individuals. Among them were Anne Boleyn (of course!), Ophelia, Juliet, Cordelia, the Lady of Shalott, Marie Antoinette, Pocahontas, Machiavelli, Columbus, Voltaire, Lorenzo de Medici, Dante, Galileo, Raphael, Michelangelo, Captain Cook, the Black Prince, Otto von Bismarck, Marco Polo, and many more! One can sense a focus on Italians, explorers, military heroes, and tragic heroines—all constant themes in Astor's life. Mr. Astor sat grandly in the middle of the room, facing the Thames, at an enormous desk that was supported by four griffin/dragon-like creatures. He was surrounded by tiger-skin rugs and elaborate furniture designed for him by John Dibblee Crace, of the famous firm of Crace & Co., the distinguished British interior designer who planned the interiors at the Royal Academy, the British Museum, and the National Gallery. And, of course, as this was the office of a very rich man, there was a secret door that led to a steel-paneled private vault, where Mr. Astor kept piles of currency, gold, and jewels (to support this enormously heavy room, which was lined with tons of steel, special pillars were required in the floors below). One of the pieces of extraordinary jewelry that made its home in the vault was a French diamond coronet comb supposedly given by Louis XIV to one his favorites and worn by Mrs. Astor when she was presented to Queen Victoria in 1893. As an added security feature for the paranoid Mr. Astor, the Great Hall was equipped with a lever that closed and locked every door in the house simultaneously (each floor also had a fire hydrant—he wasn't just paranoid about security). Happily, all of this, with the exception of the furniture and the vault, survives today. William Waldorf Astor was an avid bibliophile, which meant that there had to be a fine library at Astor House. Filled with rare volumes and illuminated manuscripts, this room was entered from the Great Room by another secret paneled door. Small and luscious, this was the most private of all Mr. Astor's spaces; very few gained admittance here. With polished mahogany floors and walls and bookcases of satinwood, this exotic space also housed a collection of letters written by famous authors like Charles Dickens, Lord Byron, and Samuel Pepys; a collection of historical musical instruments; rare chess sets; a medieval reading stand; and, very strangely, a spinning wheel next to a life-sized poupée mannequin holding a mandolin. Astor's daughter Pauline, who had stepped into the shoes of hostess for her father after her mother's death, was possibly the child he adored the most. She would frequently read historical fiction aloud to her father in the Library—the two of them gently stepping back into time. Mr. Astor's bedroom, significantly positioned next to the vault, was paneled in rare, dark Cuban sabicu wood and featured an oval ceiling. It was surprisingly small, but contained a ponderous, heavily carved French four-poster bed that almost filled the room. Sadly, the bedroom was destroyed during the 1944 bombing. After the completion of his miniature Tudor-Gothic London castle, Mr. Astor hosted a sumptuous banquet in 1895 to show off his new building to the great and good of society. In December of 1895 he commissioned the prestigious London firm of Bedford Lemere & Co. to photograph the interior and exterior of the house (these photos are valuable today as a historical record of how the house appeared when it was new and fully furnished). And in 1898 Astor House was listed as one of London's best public buildings, even though it was not a public building! Mr. Astor must have popped his buttons with pride. After the great man's death in 1919, his sons found Astor House too grand for a business office and moved the Astor Estate Office to other premises. In 1920 there was a sale of its contents, after which the slightly forlorn house was put up for sale. It remained unsold for two years. Such an idiosyncratic house needed a very special owner who could appreciate its drama and spectacle—perhaps an Indian prince or a Hollywood movie mogul! A more prosaic owner was found in 1922, when Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada purchased Astor House for £80,000—£170,000 less than it cost to build. Renamed Sun of Canada House, it served as the insurance company's British offices until they outgrew the space in the last years of the 1920s. In 1928 Astor House was rechristened as Incorporated Accountants' Hall, the headquarters of the Society of Incorporated Accountants, and in 1929 the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth) officially opened the accountants' new home amid great fanfare. The Society proved to be an exceptional and caring custodian of Astor House over the next 30 years, which proved challenging when World War II intervened. On July 24, 1944 Electra House, next door to Astor House, received a direct hit from a German V1 flying bomb. This attack also damaged the western façade of Astor House and destroyed the wing that housed Mr. Astor's bedroom. Much like the triumphant survival of the dome of St. Paul's during the Blitz, Astor House's "Santa Maria" weathervane emerged unscathed from the Second World War—a symbolic survival of London and its link with the United States. In 1949 the accountants began the post-war restoration of the house, a process that was beautifully completed in 1951. In 1959 the Society of Accountants sold Astor House to medical equipment manufacturer Smith & Nephew for £168,000. Once again, the house (which Smith & Nephew renamed Two Temple Place) fell into kind and caring hands. The healthcare company built a very sympathetic addition to their new headquarters (which looks today as if it has always been there) and shored up the foundations of the house, inserting 90-foot-piles into the soft London clay (the original pilings inserted when the house was built went down 40 feet). In 1999 Two Temple Place was purchased by the Hoare family (of banking fame) as the new home of their charitable foundation, The Bulldog Trust. Gloriously restored by the Trust, the house reopened in 2011 as Bulldog's headquarters and a venue for art exhibits and charitable events. Possibly the most public exposure the house has ever received was in 2014, when it stood in for the registry office where Lady Rose gets married in the fifth season of "Downton Abbey." The interiors of Two Temple Place have actually appeared in a number of television programs, a prime example being when it appeared as the interiors of Lord Edgware's home in the 2000 episode of "Poirot" entitled "Lord Edgware Dies." We'll leave the last word on this amazing house to no less a preservation god than Nikolaus Pevsner, founder of the ground-breaking "Buildings of England" series of books. He declared Astor House "a perfect gem," an impressive statement and the ultimate compliment from a man who was not known as a fan of Victorian architecture. Footnote: Astor House was originally situated next to the impressive Queen Anne style London School Board Offices, built between 1872 and 1876. This building was demolished in 1929 and replaced by Electra House, designed by Sir Herbert Baker (famous for his rebuilding of the Bank of England), which was itself replaced in 1996-98 by Globe House, which serves today as the headquarters of British American Tobacco. (This history of Astor House was written by Curt DiCamillo for the 2017 book, "Villa Astor: Paradise Restored on the Amalfi Coast." © 2017 Flammarion).

Collections: The contents of 2 Temple Place were sold in 1920.

Comments: "Behind the sturdy Portland stone facade, the interior has a slight strange Victoriana-meets-Disney vibe, with the otherwise straightforwardly opulent rooms (lots of marble and mahogany) adorned with bizarre details, such as the characters from "The Three Musketeers" (Astor's favorite book) on the banisters of the main staircase and the gilded frieze in the Great Hall showing 54 seemingly random characters from history and fiction, including Pocahontas, Machiavelli, Bismarck, Anne Boleyn, and Marie Antoinette." —Donald Strachan

Architect: John Loughborough Pearson

Date: 1895Architect: Crace & Sons

Date: 1892-95Architect: Frank Loughborough Pearson

Date: 1893-95House Listed: Grade II*

Park Listed: No Park

Past Seat / Home of: William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor, 1895-1919.

Current Ownership Type: Charity / Nonprofit

Primary Current Ownership Use: Mixed Use

Ownership Details: Owned and operated by The Bulldog Trust as an art gallery (open only during its annual exhibition) and event venue.

House Open to Public: Limited Access

Phone: 02078-363-715

Email: [email protected]

Website: https://twotempleplace.org/

Historic Houses Member: No