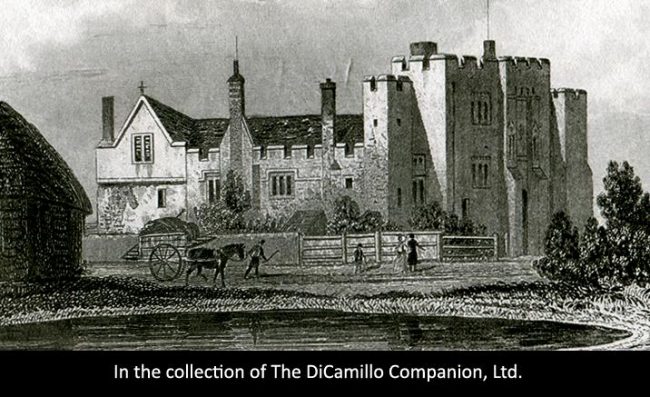

The castle from an 1845 engraving

The castle, with the Tudor Village to the left.

The castle entrance and the drawbridge

The castle courtyard with the Tudor house

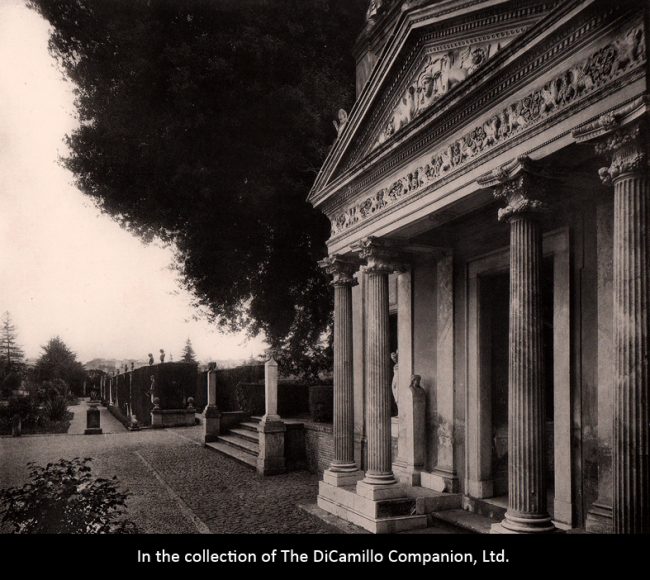

A 1906 photo of the entrance to the Bosco at the Villa Albani, Rome. Astor was inspired by Italian gardens like this in the layout out of Hever's gardens.

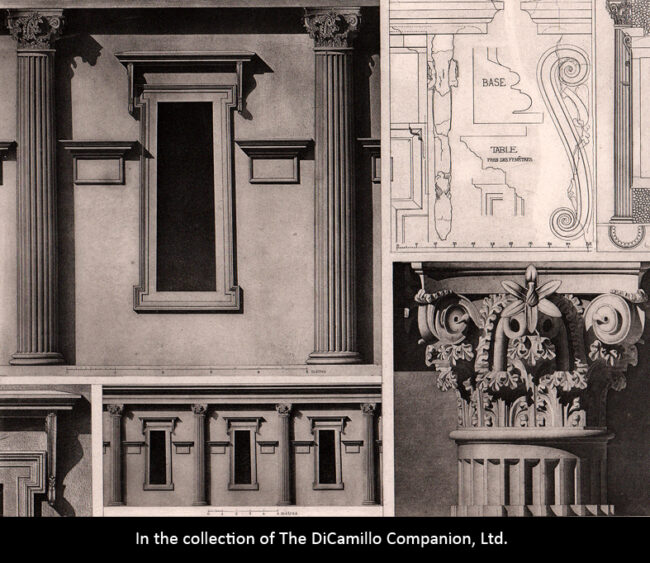

An 1890s heliogravure showing fragments from Palestrina. William Waldorf Astor was very likely influenced by the ruins of Palestrina in his garden design for Hever.

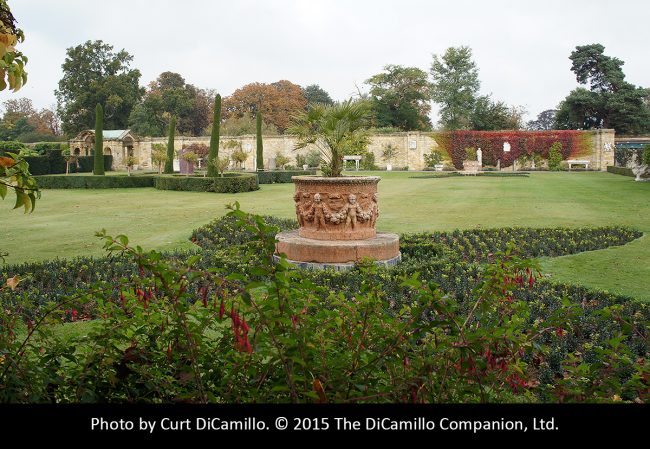

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

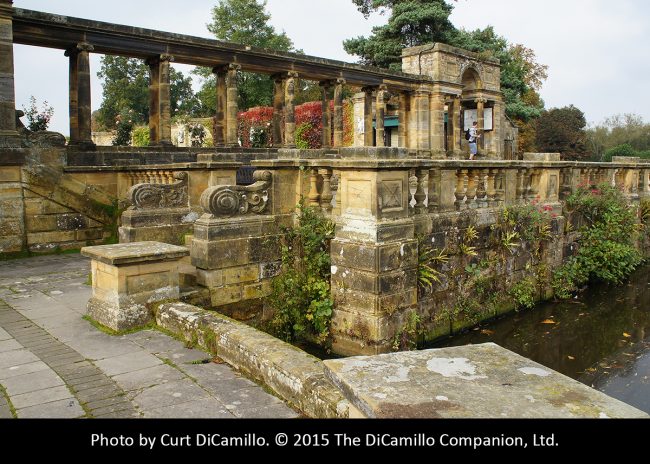

The Italian Garden Loggia

The Italian Garden Loggia

The fountain in the Italian Garden Loggia

The Trevi Fountain, Rome, which William Waldorf used as an inspiration for the fountain in the Italian Garden Loggia.

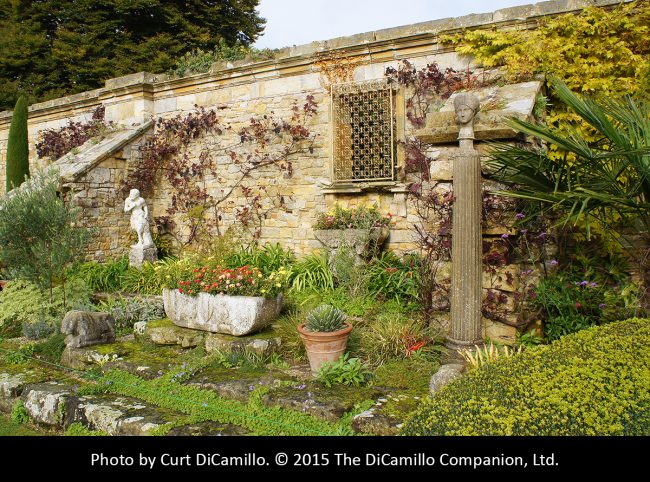

Ancient Roman urn in the Italian Garden Loggia

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The garden

The cascade in the garden

The garden

The bridge

A circa 1860 copperplate engraving of Anne Boleyn, who grew up at Hever Castle.

Earlier Houses: An earlier castle, probably 12th century, existed on the site of the 16th century manor house, parts of which were incorporated into the current house.

Built / Designed For: Bullen (Boleyn) family

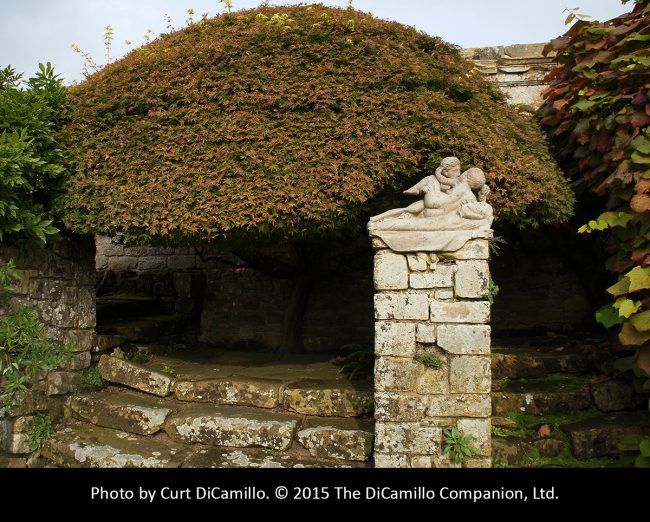

House & Family History: Tucked away in the luscious Kent countryside, the square medieval castle sits in the middle of a romantic moat, with a mock Tudor village on one side and a sophisticated Italian garden on the other. These incongruous pieces form an amazingly harmonious whole unlike anyplace else in England, all courtesy of Mr. Astor, who could easily have walked out of a Henry James novel, so much was he a part of that fin-de-siecle milieu. It was in 1903, during the reign of King Edward VII, that Astor purchased Hever and began updating and adding to the 13th century castle. The gatehouse, with the oldest working original portcullis in England (which Astor had lowered every night) is all that remains today from the 13th century; the castle Astor bought was primarily a product of 14th and 16th century rebuildings. Hever is probably most famous today as the childhood home of Anne Boleyn, second wife of King Henry VIII. The Boleyn family, who lived here from 1462 until 1539, added the Tudor manor house within the earlier castle walls, and it was here that the king courted Anne. After Anne's execution, and the death of her father, Henry VIII seized Hever and gave it to Anne of Cleves, his fourth wife, as part of her annulment settlement. The Castle later came into the ownership of the Waldegrave family, who lived at Hever for over 150 years, and the Meade-Waldo family, who sold the dilapidated old castle, by this time a farmhouse, to William Waldorf Astor. Astor, with his passionate love of history, accomplished nothing less than a total transformation of Hever, simultaneously equipping it with the latest modern conveniences while carefully respecting the integrity of its historic past. In fact, even today, Astor's work at Hever is held up as an early example of how to sympathetically restore a historic property. Hever was a staggering achievement for its time—for any time. Astor was keen to make his new house an appropriate venue for the Edwardian country house parties that were the rage during the early 20th century. And, as an American, he wanted an extraordinary level of comfort for his guests (for example, a bathroom for every bedroom—a luxurious rarity in Britain at the time), something akin to the great Newport, Rhode Island, "cottages" of the Gilded Age, with which Astor was very familiar, but with an authenticity not seen in Newport. The castle itself was too small to accommodate the many needed guest rooms and Astor, bless his soul, refused to compromise the castle's architectural authenticity by altering it, so what was the answer? A brilliantly inspired 100-room Tudor village! Connected to the castle by a covered bridge over the moat, the village was designed by the English architect Frank Loughborough Pearson, whose father, John L. Pearson, had designed Astor House on the Embankment as Astor's London townhouse. So successful was this addition that the irregular Tudor Village looks as though it was built haphazardly over the centuries—a part of the Kentish landscape that had always been there. The village contained 25 guest rooms, accommodation for visiting servants, and offices for the Hever Estate, all blended to look as though a series of cottages had been stitched together over time. Astor himself was pleased with the final result: "For a moment I could not believe that they had been built a few short months ago, they seemed so old and crooked, and possessed such individuality as though they had grown up one by one in various ages, as those old villages did which we sometimes see on our travels, sheltering themselves under the walls of the overlord." It took an enormous amount of labor to create this amazing world. By the end of 1904 there were over 500 men at work on the Tudor Village and the castle; so many workmen were required that a special train was chartered to bring them from London to Kent every day. Astor was a generous employer who paid his workers well and respected the ancient traditions of his role as lord of the manor (at Christmas each workman received two pounds of beef, a liberal amount of tobacco, and a slice of cake), but he expected his privacy to be respected in return. Nobody could enter the Hever Estate during the construction without a pass and no photography was allowed—the same terms that Isabella Stewart Gardner imposed during the erection of her great Boston palace, which was being built at the same time. When it came to the castle itself, the exterior was left untouched, but Astor and Pearson virtually rebuilt the interiors. Astor being Astor, he insisted that the interior rebuilding be done using 16th century techniques wherever possible and using only materials of the highest quality. The result was a jewel box of a house—one luscious room after another unfolds, many of them designed to highlight Astor's collection of world-class paintings, furniture, and objets d'art. Astor, who was already an art connoisseur and collector with an exceptional eye, was determined to form a collection at Hever that reflected the castle's history, as well as his own taste. Among his acquisitions was a layette very likely worked by Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth I) for the expected child of her half-sister, Queen Mary I. There are also two books of hours, both, rather exceptionally, signed and inscribed by Anne Boleyn. The collection of Tudor portraits is outstanding, with a Holbein of Henry VIII, portraits of Anne Boleyn and her sister Mary in the manner of Holbein, a portrait of Anne of Cleves attributed to Holbein, and a William Scrots of Edward VI. The fine collection of tapestries is headlined by the "Gothic Marriage," made circa 1522 at Tournai in Belgium to celebrate the marriage of Princess Mary, sister of Henry VIII, to Louis XII, King of France. This magnificent textile should always be at Hever, as it's likely that Anne Boleyn, who was attached to the French court at the time, is depicted in the tapestry as one of the ladies-in-waiting. Astor also purchased vast quantities of Tudor furniture to appropriately furnish his new castle. And, as this was an Astor home, it's only appropriate that a copy of the 1794 Gilbert Stuart portrait of the dynasty's founder, John Jacob Astor I, together with a portrait by Léon Bonnat of the man himself, William Waldorf Astor, hang on the walls of Hever. One of the undoubted stars of the collection is a 1st century AD Roman marble relief from the Arch of Claudius. This remarkable piece of high relief sculpture is a fragment of a much larger sculptural composition that decorated the triumphal arch that the Emperor Claudius erected in Rome in 51 AD, ironically enough, to commemorate his conquest of Britain. The Hever relief was almost certainly unearthed circa 1562 in the Piazza Sciarra in Rome and was considered important enough that the French artist Pierre Jacque drew it in 1576; it was later featured in the second volume of the "Galleria Giustiniana," published in 1631. Astor purchased the relief in the early 20th century from the Roman art dealer Attilio Simonetti, from whom he bought many antiquities. Originally located in the Italian Garden at Hever, the relief was moved inside the castle after it returned from the famous "Treasure Houses of Britain" exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1985. The English architect Philip Tilden, who visited Hever soon after the restoration was completed, described it as "a miniature Metropolitan Museum of New York." It's not too much to suggest that Tilden was influenced by Hever when he restored Chartwell, also in Kent, for Winston Churchill in the 1920s. Avray Tipping, the respected and influential editor of "Country Life" magazine, the bible, then as now, for country houses and country living, wrote, in a 1907 article in the magazine, "We have come across no other examples of these reproduced Jacobean ceilings where the old feeling and the old surface have been obtained to anything like the extent we find at Hever in several rooms. The attempt is most praiseworthy." The extensive interior work involved the re-arranging and conversion of many rooms. The best example of this is probably the Great Kitchen, which became Astor's Inner Hall, famous today for its exuberantly carved Italian walnut woodwork that mixes Gothic and Renaissance styles, complete with an elaborate gallery modeled on the screen of King's College Chapel, Cambridge (much of the carving at Hever, of the highest quality and using the most expensive and exotic woods, was by William S. Frith, who also worked on Astor House in London). The oak-paneled Drawing Room, inlaid with holly and bog oak, is based on the famous 16th century Inlaid Chamber from Sizergh Castle in Cumbria. The Sizergh room is famous because it was sold in 1891 to the South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria & Albert Museum) and became the institution's first period room (the Inlaid Chamber returned to Sizergh in 1999 on long term loan from the V&A). The 16th century Long Gallery, with its stained glass windows that feature the coats of arms of the families who've owned Hever through the centuries, was restored by Astor and topped off by four solid silver chandeliers commissioned in 1906—copies of chandeliers at Hampton Court Palace. But possibly no room at Hever is more sumptuous and bursting with famous inspiration than the Library. The paneling, by Frith in the style of Grinling Gibbons, and the bookcases are made from exotic South American sabicu, a naturally scented wood harder than mahogany (sabicu is so dense it sinks in water), with floors of Spanish mahogany and Swedish pine. The bookcases were based on those of Samuel Pepys (today at Magdalene College, Cambridge), while the ceiling was copied from a ceiling at Hampton Court. The 2,500 volumes, all collected by Astor and bound in Morocco leather and calfskin, still line the walls. Astor loved this kind of stuff! He was a master at successfully integrating disparate elements, often inspired by famous and royal houses, and then adding in references to history and literature for good measure. In Pearson he found an architect who was extremely capable and talented and who intuitively understood and shared his client's passion. They were the perfect team and what they left behind for us is nothing short of a masterpiece. But possibly Astor's most innovative legacy at Hever is the 125-acre garden, created with a sophisticated and cosmopolitan eye and today one of the great gardens of the world. In addition to traditional English garden elements—herbaceous borders, a yew maze, woodland walks, a pergola, a rose garden (with 3,000 roses), and a cascade—there also exists an exuberant outpost of Rome! Clearly inspired by gardens of Italian Renaissance villas like the Villa Albani in Rome, with which Astor was very familiar, the great collector filled his garden with antique Roman and Italian Renaissance statues, wellheads, sarcophagi, and columns—many of them carved from exotic stone and purchased during his time in Italy. Numerous pieces are of such a high quality that they would find pride of place in the galleries of the world's finest museums. Laid out between 1904 and 1908 by the firm of Joseph Cheal & Son, it took more than one thousand men to bring the garden to reality, aided by a narrow-gage railroad and steam shovels. The steam shovels were needed for the creation of the 35-acre lake, the excavation of which took the effort of 800 men. At one end the lake is joined to the Italian Garden by a formal loggia, complete with a fountain based on the Trevi Fountain in Rome. Astor was so determined to create a significant garden in record time that he erected a temporary village to house many of the workers and built a small cottage for himself, for he was no absentee grandee creating from afar—he was onsite almost every day supervising, suggesting, and engaging with his workers on his creation. The garden became famous and fulfilled its founder's vision of wide appreciation when William Waldorf Astor's son, John Jacob Astor V, purchased the newspaper "The Times" in 1922. John Jacob, an extraordinarily generous man, regularly held parties in the garden exclusively for employees of "The Times." Special express trains were arranged to bring thousands of the newspaper's employees from London (one year more than four thousand staff members came to Hever!) to experience the spectacular Kentish garden. Every kind of activity was available: bathing and rowboats on the lake, tennis, a flower show, golf, tours of the castle, a treasure hunt, and dancing on the lawn. I suspect that William Waldorf Astor would have been very proud that, in 1995, his garden won the Historic Houses Association/Christie's award for the best garden in Britain. In 1968 there were catastrophic floods in Kent when huge rainfall caused the River Eden to overflow its banks. Hever, lying in low ground, was overwhelmed—so quickly did the water rise that the staff at Hever had to be evacuated by boats. Contents that weren't moved to the upper floors of the castle to escape the deluge were ruined. It took years for Hever's rooms to dry out; the restoration of the interior wasn't completed until 1972. Eleven years later the Astor family sold Hever Castle to Broadland Properties, who operate the castle today as an upscale hotel, conference center, and visitor attraction. And, of course, like most British castles, Hever is supposedly haunted! The castle, not surprisingly, is visited by the ghost of Anne Boleyn, who roams the rooms on stormy nights. And sometimes, very late at night, mournful love songs can be heard emanating from rooms where Henry VIII romanced Anne. Writing anonymously in a 1907 article in "The Pall Mall Magazine" entitled "Hever Restored," Astor (who owned the magazine) described his recently restored Kent estate as "the daintiest of castles, a castle in miniature, a castle-ette, of the feminine gender." It was a castle he had rescued from "the possession of humble farmers whose ducks and geese swam in the old moat, whose kitchen were the once proud Hall, who bacons and hams hung seasoning from the ancient beams, whose spades and shovels and hoes were piled in the ancient guard house, whose corn and potatoes lay stacked in the chambers that were haunted by so many memories." In closing, the more I researched Astor the more I came to believe that this man, often called aloof and serious, had a sweet and romantic core at the center of his being. And I think it was this nature of his character that led him to purchase and restore with such love and compassion places like Hever. (This history of Hever was written by Curt DiCamillo for the 2017 book, "Villa Astor: Paradise Restored on the Amalfi Coast." © 2017 Flammarion).

Collections: Some contents were sold on May 5, 1983, including Giovanni Paolo Negroli's suit of three-quarter armor made for Henri II of France, which was sold to Rothschild Reserve International of New York for £1,951,250. A Flemish suit of three-quarter armor belonging to the 3rd Earl of Southampton was sold from Hever and purchased by the Royal Armouries for display at the Tower of London. The collection at Hever includes two books of hours, both signed and inscribed by Anne Boleyn. There is also a fine collection of Tudor portraits, tapestries, and furniture. One of the stars of the collection is a 1st century AD Roman marble relief from the Arch of Claudius. This remarkable piece of high relief sculpture is a fragment of a much larger sculptural composition that decorated the triumphal arch that the Emperor Claudius erected in Rome in 51 AD, ironically enough, to commemorate his conquest of Britain. The Hever relief was almost certainly unearthed circa 1562 in the Piazza Sciarra in Rome and was considered important enough that the French artist Pierre Jacque drew it in 1576; it was later featured in the second volume of the "Galleria Giustiniana," published in 1631. Astor purchased the relief in the early 20th century from the Roman art dealer Attilio Simonetti, from whom he bought many antiquities. Originally located in the Italian Garden at Hever, the relief was moved inside the Castle after it returned from the famous "Treasure Houses of Britain" exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1985-86. On April 28, 2003 five miniature portraits, worth about £100,000, were stolen from Hever; the stolen pieces included two of Mary, Queen of Scots; Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, Henry VIII's adviser who was executed for treason in 1540; Queen Mary; and Anne of Austria, the wife of Louis XIII.

Comments: "Nowhere is Edwardian craftsmanship displayed with more extravagant panache, yet without damaging the medieval exterior." —John Newman, "The Buildings of England: West Kent and the Weald"

Garden & Outbuildings: Between 1904 and 1908 William Waldorf Astor further enhanced the Castle's romantic setting by creating glorious gardens, with much of the work designed by Joseph Cheal & Son; these include the Italian Garden (designed to display Astor's collection of Italian sculpture, which ranged from ancient Roman to the Renaissance), the Yew Maze, the 35-acre lake, and the Rose Garden. The Italian Garden took over two years to construct, with over 1,000 men working continuously on the project; it took 800 men to dig out the lake at the far end of the Italian Garden. The Rose Garden (with over 3,000 plants), the Tudor Herb Garden (opened in 1994), the Yew Maze, and the 110-meter herbaceous border have all won awards. Hever was also the winner of the HHA/Christie's Garden of the Year Award in 1995. The grounds also contain the Two Sisters Pond, the Half Moon Pond, the Cascade Rockery, and a formal loggia fountain based on Trevi Fountain in Rome. In the late 20th century the Millennium Fountain was added on Sixteen Acre Island. Hever is not far from Ashdown Forest in East Sussex, which was the model for The Hundred Acre Wood of the Winnie-the-Pooh stories.

Architect: Joseph Cheal & Son

Date: 1904-08Architect: Frank Loughborough Pearson

Date: 1903-06Country Life: II, 266, 1897. XXII, 522, 558, 1907. XLVI, 511, 1919. CLXIX, 18, 66, 1981.

Title: Movie Locations: A Guide to Britain & Ireland

Author: Adams, Mark

Year Published: 2000

Publisher: London: Boxtree

ISBN: 0752271695

Book Type: Softback

Title: Disintegration of a Heritage: Country Houses and their Collections, 1979-1992, The

Author: Sayer, Michael

Year Published: 1993

Publisher: Norfolk: Michael Russell (Publishing)

ISBN: 0859551970

Book Type: Hardback

House Listed: Grade I

Park Listed: Grade I

Past Seat / Home of: Sir John de Cobham, 14th century. Sir Geoffrey Bullen (Boleyn), 1462-63; Boleyn family here 1462 until 1539. Anne of Cleves, 1540-57. Waldegrave family, 1557-1717. Meade-Waldo family, 1749-1903. William Waldorf Astor, 1st Baron Astor and 1st Viscount Astor, early 20th century; Astor family here 1903-82.

Current Ownership Type: Corporation

Primary Current Ownership Use: Mixed Use

Ownership Details: Owned by Hever Castle Ltd. (part of John Guthrie's Broadland Properties group) and used as a visitor attraction, conference center, and hotel.

House Open to Public: Yes

Phone: 01732-865-224

Fax: 01732-866-796

Email: [email protected]

Website: https://www.hevercastle.co.uk

Awards: Christie's/HHA Garden of the Year Award 1995.

Historic Houses Member: Yes